"It seems as if nobody is asking classroom teachers what will be most helpful"

I was drastically underprepared for my first teaching position.

It was the early 1990s, and I had just graduated with a B.S. in mathematics and a split minor in physics and electrical engineering. While investigating my graduate school options, I secured a part-time job leading the after-school math and science activities for 2nd through 9th graders at Friendly House, a Hispanic community center in downtown Phoenix.

I had grown up less than 30 miles away in suburban Mesa, where expectations were drastically different. I had gone home after school to a snack and a quiet study area; my Friendly House students came to a crowded community center and worried whether they could afford a pencil.

And the most telling difference? My high school physics teacher was an award-winning Woodrow Wilson fellow with a deep scientific background. In contrast, my Friendly House colleagues recalled a physics classroom staffed by a teacher with no training in physics, where time was spent watching documentaries narrated by Star Trek’s Captain Picard rather than performing scientific investigations.

Preparation

How might we ensure teachers enter the classroom well-prepared to teach STEM?

Almost 30 years later, I continue to be surprised by the inequities between schools only a short drive from one another. In 2007, I watched as thousands of education dollars were spent replacing American flags in good condition. A state legislature ruling had dictated a flag with a “minimum size of 2-feet by 3-feet,” so the flag in my classroom (and every classroom in a district employing almost 1000 teachers) was exchanged for a larger flag. But funding did not extend to provide meaningful support and training for the many teachers leading STEM classes outside of their content areas.

Much of the professional training I have experienced as a teacher has not had much impact upon my day-to-day practice. Some has focused on the outliers rather than the meat of my teaching: Hours spent on how to detect drug use (important, but not my primary job) rather than how to use electronic data collection probes (needed frequently in my classes). In other cases, training was marginally useful but fell short of the rich scientific discourse for which I strived: In-service days detailing simple strategies to encourage student cooperation (like think-pair-share and jigsaw), but not including examples to inspire deep learning in STEM fields.

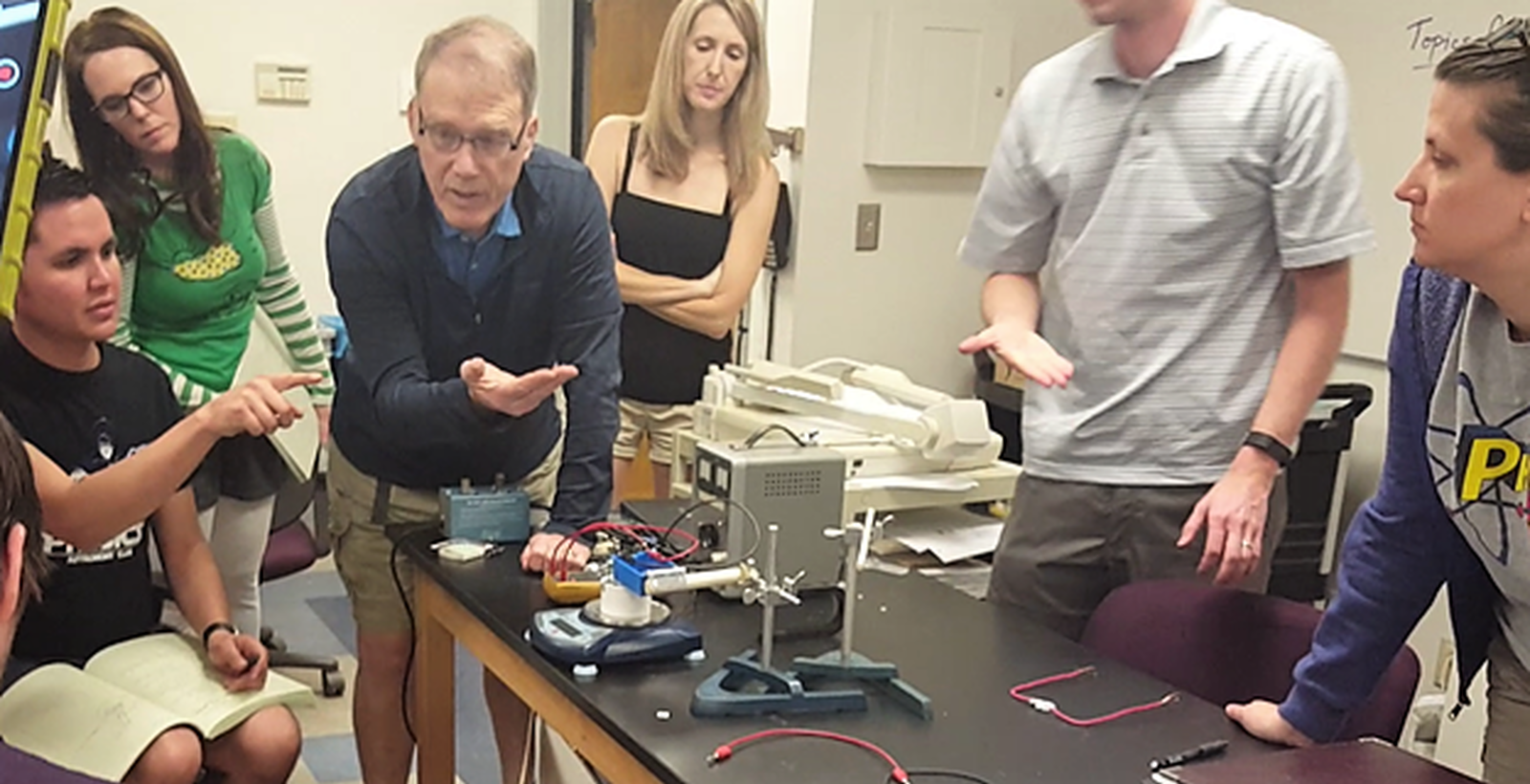

After my first-year of teaching, I was lucky to spend three consecutive summers in a National Science Foundation funded program, Modeling Instruction, where veteran high school instructors trained physics teachers from across the country to implement effective practices in their classrooms. I have been leading and participating in similar summer professional development since then, typically supported by short-term grants or donations rather than state funding, and is therefore inaccessible to most teachers.

This initial training, along with my continued participation in the Modeling Instruction program, has been the single most important factor in improving my classroom practice. Each summer I witness the transformative effect of excellent content-based professional development on overwhelmed teachers. I work with colleagues to convert our classrooms to prepare the mathematicians and scientists of the future. Our students are doing science, not just learning about science, and both teachers and students find joy in the process.

WHAT CHALLENGES HAVE YOU ENCOUNTERED IN YOUR CAREER AS A STEM EDUCATOR?

Imagine a world where your doctor had never practiced the new procedure she was about to use, your mechanic had never trained on a vehicle less than 10 years old, and your cell phone provider did not offer 4G because technicians were not prepared to update infrastructure.

Imagine the only in-house training provided for doctors, mechanics, or technicians was led by motivational speakers with minimal experience in medicine, automotives, or communications technology.

Imagine each doctor, mechanic, and technician was told that if they wanted to support recent developments in their field, they must pay for their own training with no guarantee of equivalent compensation when they secured a position or returned to their job.

Covering broad ideas in educational theory without specific examples in science or math content is ineffective.

These are the parameters governing many current teacher preparation programs and educator training opportunities. I have encountered Methods of Teaching Science courses which do not address any science content. I have attended district-supported training provided by pricey consultants with drastically less experience in a K-12 classroom than many of their teacher-participants.

Covering broad ideas in educational theory without specific examples in science or math content is ineffective. Teachers are better served by learning from fellow teachers with decades of classroom experience in their STEM field. They should be doing STEM in preparation programs, and then dissecting the typical student difficulties involved. Educators must practice constructing their own STEM learning communities and then repeat the process with students in their classrooms.

Such high-quality transformative experiences (which support and retain excellent teachers) are available. But unfortunately, many of these programs lack the support needed to be sustainable. Educators are unable to participate because their schools cannot afford to organize such trainings, and teachers cannot meet the expense of forgoing summer employment while paying for workshop registration themselves.

High profile programs dedicated to temporarily placing teachers in the classroom have massive support, while preparing and rejuvenating our existing committed workforce is often neglected. And it seems as if nobody is asking classroom teachers what will be most helpful—as if teachers themselves are untrustworthy in identifying and solving the problems they encounter every day.

I have a challenge for organizations such as 100Kin10 and its partners: Consider looking beyond the quick fix or the current pet cause promising to repair the system. Do not be distracted by headline-grabbing initiatives. Instead dedicate resources to the sustained support critical to training our teachers and preparing our kids for the economy of the future. Commit to the goal of rejuvenating and transforming dedicated professionals already in the system.

And most importantly—if you want to promote STEM education, begin by asking a practicing STEM teacher what support they and their students really need.